Pandemic: a capital experience

- Nichole Overall

- Mar 24, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 21, 2020

“All persons travelling from infected areas [are] asked to submit themselves to an inhalation chamber”.

Masks normally the domain of health professionals are donned by the public and proclamations issued on everything from travel restrictions to school closures and the cancellation of public events.

Communities disrupted, social cohesion fragmented, economies impacted. Whispers of the end of the known world.

No, it’s not COVID19, but a 101-year-old peril - the deadly Spanish Flu, or more accurately, the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19.

Having made landfall in Australia as early as November 1918, within two months it had descended on the Canberra region.

In less than two years, the previously unseen ("novel") disease circulated the globe (the two qualifications of a pandemic), causing as much as six times the carnage of the world-shattering war it emerged within. Carried far afield by those who remained, little preparedness, low immunity and no effective vaccines saw millions upon millions die; according to one of its early researchers, Texan historian Alfred W. Crosby, “Nothing else - no infection, no war, no famine - has ever killed so many in as short a period”.

It was late January, 1919, before the flu was officially acknowledged as having breached the believed protected shores of Australia. What it was and how it should be dealt with became a matter of debate. While today we’re witnessing the stockpiling of ‘loo paper and body-sized bags of rice, back then it was wearing red wrist bands, the colour believed to ward it off, and taking laxatives to “flush” out the system.

War-time censorship, misdiagnosis and press influence all contributed to the general confusion and misinformation, and the local experience alone is telling.

The inhalation chamber as a precautionary measure was proposed at an Influenza Committee meeting in Queanbeyan on April 4, 1919.

Back in February, The Queanbeyan Age was expounding that “The unforced conclusion is that the epidemic which caused so much havoc has spent its force, and that the worst Australia has to face is the continuance of an influenza which it has been familiar with for years.”

This appeared alongside an advertisement for free (essentially useless) inoculations - along with Queanbeyan, depots at Oaks Estate, the Canberra Hospital, Hall, Majura Recreation Hall, Tuggeranong School and Tharwa.

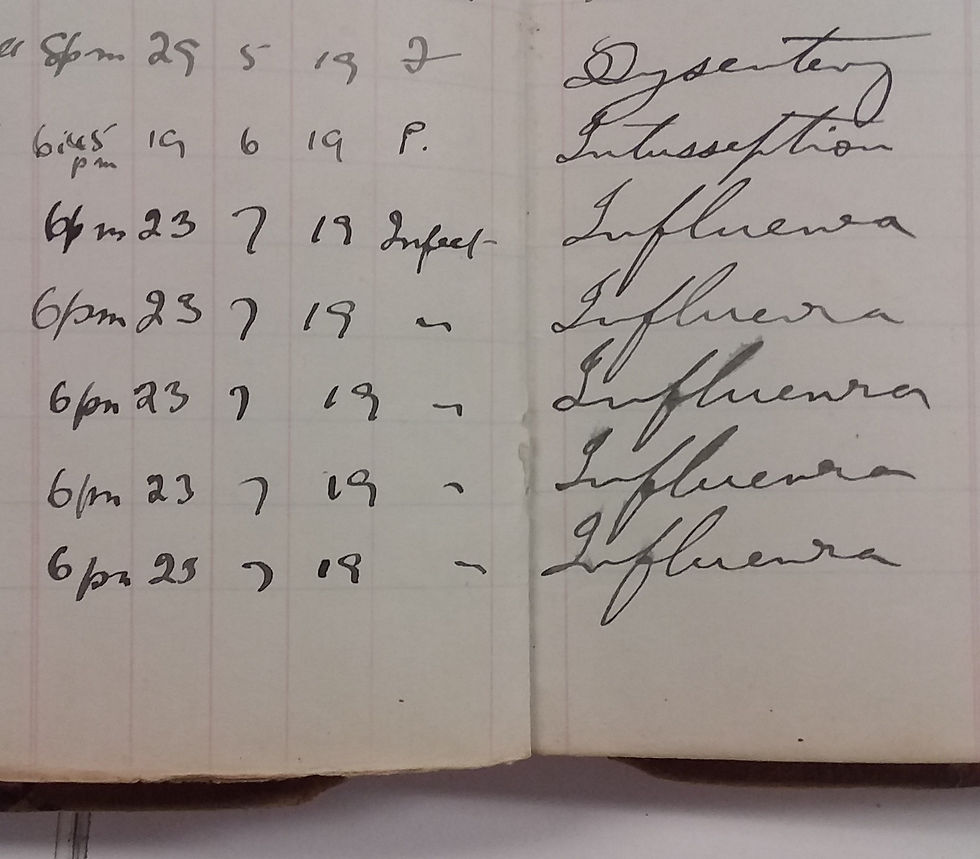

On March 28, the long-running newspaper (est. 1860) also refuted reports of “a case of pneumonic influenza in Queanbeyan” claiming it was “absolutely false”. Truth is, there’d been at least one death in the Queanbeyan Hospital as early as January 13. It was recorded that Marion Dunlop, 45, of Bungendore, had died of “double pneumonia”: what wasn’t recognised at that early stage was that “pneumonienza” paved the way for such secondary infections.

Elsewhere around the region, a young mother and her newborn daughter became Goulburn’s first official victims on April 17 (it's suggested some of the highest mortality rates were among pregnant women and academic Elizabeth Outka has recently stated in five years of research, she only came across a single case of survival in these circumstances - the wife of Irish poet, W.B. Yeats).

Another 33 of its residents would be dead by the end of May - including the town’s Health Inspector, J.R. Biddle. At the same time, Michelago intended on using its School of Arts building as a hospital, there were recorded instances in Yass, Bungendore and Braidwood, and multiple deaths in Cooma - seven within 48 hours, aged between 17 and 34, four of whom were siblings.

Still though, The Queanbeyan Age was holding out. In mid-June it stated: “The present weather conditions are responsible for an epidemic of colds and catarrhal infections; but fortunately so far there has been no symptom of pneumonic influenza in the neighbourhood of Queanbeyan”.

Less than a month later, the editorial tone was vastly changed. Page two pronounced that influenza was “now raging” in the town and the Public Health Department had been twice telegrammed with the request for another four nurses and an additional doctor to cope.

While a Fever Ward had been added to the town’s District Hospital in 1885, a separate “Plague Ward” didn’t commence construction until 1919. Proposals for local emergency hospitals included the Queanbeyan Showground Pavilion and the “Molonglo Concentration Camp” - itself hastily built on the plain separating Queanbeyan from the Federal Territory (Fyshwick) for the internment of “alien enemies” during WWI.

At the on-again-off-again, five-year-old “temporary structure” that was the Canberra Hospital at Acton (now, the ANU), half of its eight beds were occupied by infected patients. Returning servicemen were quarantined for 10 days there in specially erected tents rather than the Isolation Block. Others were apparently “being treated in their own homes”. Some ignored the requirements entirely, much to the chagrin of authorities.

The restrictions and effects were far-reaching: in the same year the Royal Easter Show in Sydney was cancelled, so too, the Queanbeyan Show. By year end, of the still new nation’s population of 5 million, it’s estimated 2 million were infected, and up to 15,000 died. Of course, the true figures can never be known. How much worse though, might it have been?

Although some of the early editorial content put forward by The Queanbeyan Age was contrary to the wider public good, eventually the advice became more sensible - and in our current environment, bears repeating.

“We can refuse to be ‘stampeded’ by unworthy panic and summon to our aid that courage which is equally heroic in endurance as in action … Is it not true, at all times and in all places, that panic is more dangerous than the circumstances which apparently produce it?”.

Alternatively, if we’re going to insist on hoarding toilet paper, might as well make use of it and give those laxatives a try.

* Interview on 2CC about the local experience:

SOURCES:

* Brigid Whitbread - Queanbeyan Library

* Trove

* rahs.org.au

* heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au

* Royal Canberra Hospital, complied by Arthur Ide, 1994.

Comments